Our Story

Founded in 1874 as the Cotuit Lyceum Society “for the diffusion of useful knowledge and by procuring lectures, instituting debates and thereby inducing habits of thought,” the Cotuit Library has been proudly providing library services and a gathering space for the village of Cotuit and surrounding towns for 150 years.

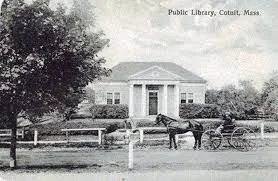

During its early years, members of the Cotuit Lyceum Society began to acquire books for the collection, which was first housed in Asa Bearse’s store, then moved to Freedom Hall. In 1894, the Cotuit Library Association was formed, and the collection moved to the former Schoolhouse Number 11— constructed in 1830— today’s current entry room. Through the years, myriad expansions to the old schoolhouse have allowed the collection to grow. In 1901, renowned architect Guy Lowell designed the addition along with the charming and memorable façade of the library that faces Main Street in Cotuit to this day.

Founder Spotlight:

Lucy Gibbons Morse (1839-1936)

An intellectually active and civic-minded woman of the 18th and 19th centuries, Lucy Gibbons Morse felt it important that the community have a library. In keeping with her activist background, literary and artistic prowess, and interest in education for all, she was instrumental in founding the Cotuit Library. She served as a member of the library’s board until 1923.

-

Born in New York City, Lucy Gibbons was one of four children of Abigail Hopper (1801-1893) and James Sloan Gibbons (1810-1892), members of the Hicksite branch of the Quaker Society of Friends. Lucy grew up in a home fueled by social activism.

Lucy Gibbons Morse grew up in a turbulent era. After the war years, she became involved in literary pursuits and met educator and schoolmaster, James Herbert Morse, whom she married in 1870. Together they had three children, Rose Morse, William Gibbons Morse, and James Herbert Morse, Jr.

A graduate of Harvard University, James Herbert Morse Sr. specialized in teaching preparatory courses for entrance exams to Ivy league universities. Morse helped prepare a number of his students, as well has his own children, for the Harvard entrance exams. Knowing that the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, summered in Cotuit, Morse purchased a home in Cotuit in 1879 and established a summer school for students who wanted to get into Harvard.

An intellectually active and civic-minded woman of the 18th and 19th centuries, Lucy Gibbons Morse felt it important that the community have a library. In keeping with her activist background and interest in education for all, she was instrumental in founding the Cotuit Library. She served as a member of the library’s board until 1923.

Buried in Cotuit, Lucy Gibbons Morse left a legacy of artistic and literary talent as well activism and philanthropy.

-

Lucy’s mother, Abigail ‘Abby’ Hopper, was an abolitionist, schoolteacher, and social welfare activist. Hopper grew up in a Quaker family in Philadelphia, and her father, Isaac Hopper, opposed slavery and aided fugitive slaves. He often directly confronted the slave kidnappers who frequented Philadelphia sometimes kidnapping free blacks for sale into slavery and capturing fugitive slaves to gain bounties. Called upon to protect the rights of African Americans, Isaac Hopper and his wife garnered a reputation as friends and advisers of African Americans in all emergencies. The Hoppers also sheltered many poor Quakers in their house, despite their own family’s large size and their unstable financial status. Hopper served as an overseer of the Negro School at Philadelphia and as a volunteer teacher in a free school for African-American adults.

Abby Hopper shared her parents’ anti-slavery beliefs. As a young woman, she taught school for several years in Philadelphia. In 1833, she married James Sloan Gibbons, a fellow Hicksite Quaker from New York, who was also an ardent abolitionist. In 1835, they were forced to move from Philadelphia because of their anti-slavery, abolitionist activities, and in 1836 the couple moved to New York City, where they had six children. Two of their sons died in infancy. Their daughters included Sarah Emerson Gibbons and Lucy Gibbons.

As well as his standing as a prominent Quaker and outspoken abolitionist, James Sloan Gibbons was a cousin to Horace Greeley, founder and editor of the New York Tribune, among the great newspapers of its time. In 1841, the Quakers disowned Isaac Hopper and James Sloan Gibbons (Abby’s father and husband) for their anti-slavery writing. One year later, she resigned and removed her children from the group.

Abby Hopper Gibbons was prominent during and after the Civil War (1861-1865). Her work in Philadelphia, Washington, DC and New York City included civil rights and education for blacks, prison reform for women, medical care for Union officers during the war, aid to veterans returning from the war, and welfare. Because she was a known abolitionist, their family house -a recognized station on the Underground Railroad- was among those attacked and destroyed during the New York City draft riots of 1863.

-

By the late seventeenth century, cut-paper portrait silhouettes became widespread in England, France, and Germany. Also known as shades, profiles, and shadow pictures, they were ubiquitous because of their affordability. Silhouettes were cut by prominent artists, including August Edouart (1789–1861), Raphael Peale (1774-1825), and Rembrant Peale (1778-1860), as well as by itinerant portraitists and amateur artists. They were often made using a tracing device to render shadows, but more skilled artists could cut portraits freehand.

Influenced and inspired by her family’s paper portraits cut by the famed silhouettist Auguste Edouart, Lucy Gibbons Morse became an adept artist in her own right in the medium of cut paper. Using surgical scissors, Morse cut intricate and delightful silhouettes of local flora, peopled with imaginative fairies, a popular subject in her time. During the Victorian era (1837-1901) the artistic and literary communities experienced an outpouring of fairy paintings, fairy tales and works of fantasy and nonsense. Victorians were haunted by the fairies of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream and of European folklore; fairyland allowed an escape from their era’s concerns. Rural superstitions about an uninhibited tiny people, over whom flowers towered and gravity’s laws held no sway, provided a charming antidote to unsettling advances in scientific understanding and industrialization. For artists and writers, the imagination’s powers were vindicated by the notion of a kingdom that only the inner eye could see.

The artwork of Lucy Gibbons Morse combined excellence in paper cutting with the Victorian interest in fairies. In her animated world of nature and enchanted childhood innocence, the sprites and little folk dance and frolic. She mounted black paper cut silhouettes between silk panels that she bordered with cord to be used as lampshades and light covers; when lit from behind with candles or gaslights, the flickering light created a sense of movement and the impression that the fairies had come to life.

In 1921, she published the book, Breezes, a collection of silhouettes and stories for children. A skilled writer and storyteller, Lucy Gibbons Morse had previously published a children’s book- The Chezzles (1888); Rachel Stanwood: A Story of the Middle 19th Century (1893); as well as other collaborative works. poetry, and short stories